Hello, this is Eureka.

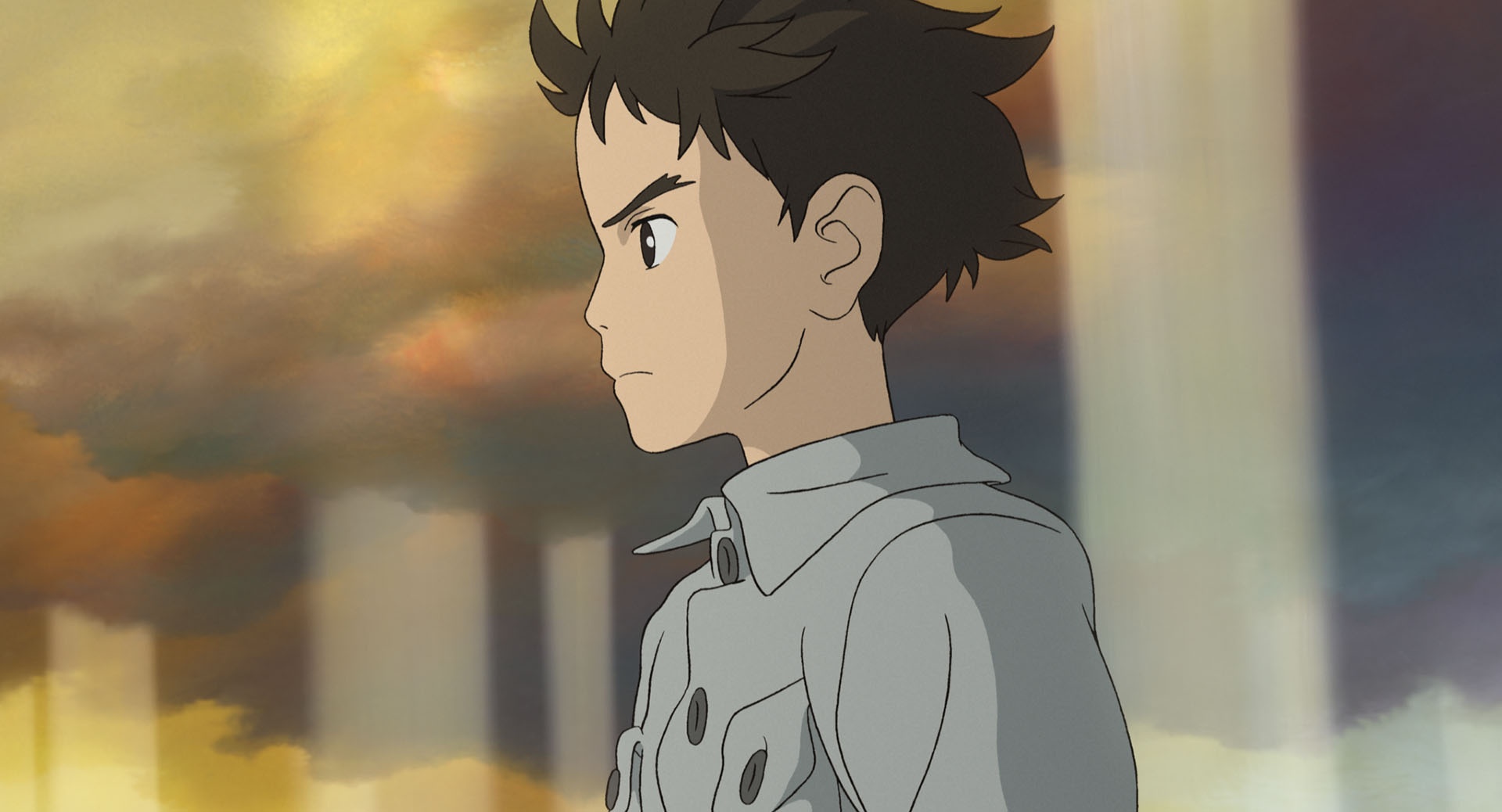

Today I will be analyzing and reviewing Studio Ghibli’s latest film, ‘The Boy and the Heron’, released under the original Japanese title ‘How Do You Live?’

[Addendum]

On January 8th, 2024, the film won the Golden Globe Award for Best Animated Film. This marks the first time a Japanese animation has won this award, making it a groundbreaking achievement.

- ‘The Boy and the Heron’ is director Hayao Miyazaki’s first film in 10 years for Studio Ghibli.

- [Act One] An Imprisoned Mother | The Scars of War on Mahito

- Mahito’s Circumstances | Losing His Mother and Home in the War

- A One-Sided Reality | His Father Remarries (Pregnancy)

- Encounter with the Heron | Folk depictions of bad luck flying into the house

- Mahito’s Reality | His “Mother” Trapped in Flames, Mysterious Stone Tower Discovery

- Mahito’s Loneliness | Accelerated Not By His “Aunt” But His “Father” → Injured Through Malice

- Mahito’s Frustration | Knowing But Unable To Take The “Right” Action

- [Act Two] Rescuing “Mother” (1)

- Mahito’s actions (1) Weapons manufacturing|Solutions learned from his “father

- Mahito’s Behavior (2) Reforming Bad Intentions|Solutions Learned from “Mothers” = Genzaburo Yoshino, “How Do You Live?

- [Remarks] Hayao Miyazaki’s Experience|The One Thing He Couldn’t Say

- Change in Manato|Going to the stone tower for his aunt (a token of his malice)

- [Act Two] Rescuing “Mother” 2 | To the Spirit World

- Storyline | Meeting Young Kiriko at the Shore → Setting Off With the Heron

- Meaning of the “Shore” | Between Life and Death

- Meaning of “Those who learn of me die” | Grave (Iwakura) of Malice

- Yamato Takeru Legend ‘Fire Attack, White Heron’ | What the “White Heron” Symbolizes

- True Identity of the Warawara | Hints in Kiriko’s Dialogue

- True Identity of the Pelicans | Fate of Those Who Pile Up “Petty Malice”

- [Act Two] Rescuing “Mother” 3 | Mahito’s Answer

- Mahito Meets Himi | Backstory on the “Stone Tower”

- Mahito’s Resolve | To Return Home Together with Natsuko

- The Director’s Intent | Spotting Toyotama-hime Mythology in the Birthing Hut

- [Anecdote] Another Myth From the Kojiki & Nihon Shoki | Why So Much “Fire” Imagery

- The Reason for Natsuko’s Rejection of mahito at the Maternity Hut

- [Side Note] Why the Inside of the Stone Tower Feels “Prickly”

- mahito’s Growth – Why He Calls Natsuko “Mother”: Connecting “Malice” with “Sincerity”

- The Uncle’s Objective – Jungian Dream Analysis

- The Fight Over the “Stone Tower” – The Great Uncle Who Wants a Successor vs. The Tanuki Lord Who Wants Control

- The Collapse of the “Stone Tower” and mahito’s Decision – Confessing His Own “Malice”

- [Act Three] Parting from “Mother” and “Return”

- mahito’s Parting – His “Mother” Himiko

- mahito’s Return 1 – His “Mother” Natsuko

- mahito’s Return 2 – Why He Brings Back “Stones of Malice” = Empathy Toward the Pelicans

- [Side Note] Spiriting Away Trope – Memory Loss = Blue Heron’s “You’ll Forget Anyway”

- Epilogue – Returning to Tokyo 2 Years After the War’s End, With a Younger Brother Born Safe and Sound

- [Consideration] “Add One of the 13 Blocks Every 3 Days” – The Great Uncle as Psychologist Carl Jung

- The Great Uncle’s “Stone Tower” – Connection to Psychologist Carl Jung

- [Addendum] Interview Between Hayao Miyazaki and Bin Kimura

- 13 Stone Blocks = the 13 Years Since the Great Uncle Disappeared

- Meaning of “Add One Every 3 Days” – Time Differential Via Spiriting Away = Inside and Outside the Tower

- mahito calculates: 2 days = 8 months

- 8 months after in reality = End of war | Fighter plane windshields “cleaned up”

- [Notes] Unused Fighter Planes | Kamikaze Special Attack Units

- 【Reference site list】

‘The Boy and the Heron’ is director Hayao Miyazaki’s first film in 10 years for Studio Ghibli.

Details About the Film ‘The Boy and the Heron’

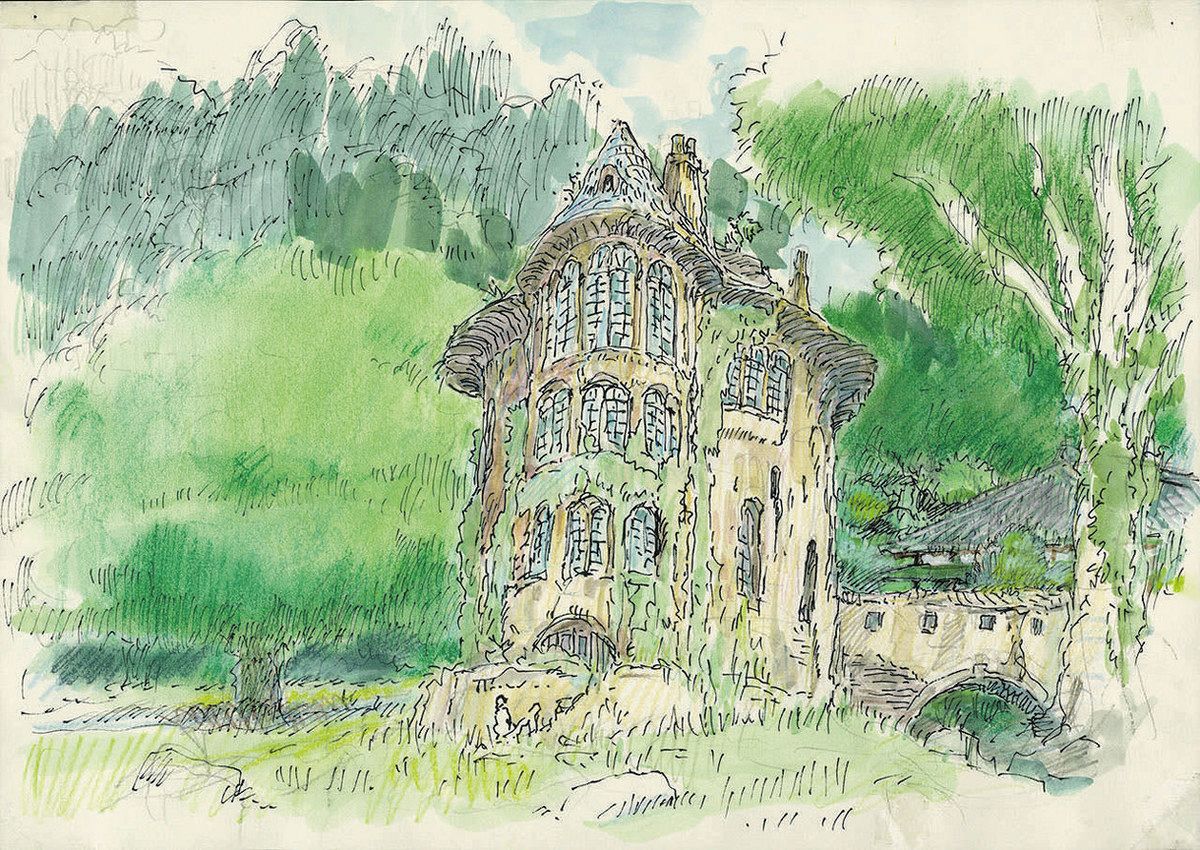

This film is Miyazaki’s 12th theatrical feature film as director. However, despite its impending release on July 14th, 2023, no trailers, advertisements, or even posters had been revealed, making this an exceptionally unusual situation for a film’s launch.

– On June 16th, 2023…It was announced the film would screen in Dolby Cinema and Dolby Atmos

– On July 7th, 2023…It was announced the film would screen in IMAX

These screening format announcements also came very close to the release date. This marks the first time a Studio Ghibli film has been screened in IMAX.

[Background on the Title] Based on the novel ‘The Boy and the Heron’ by Genzaburo Yoshino

Before the release, only two details about the film were known:

1. An original work by director Miyazaki with no existing source material

2. The genre is adventure fantasy

The title comes from Genzaburo Yoshino’s novel ‘The Boy and the Heron’ but it is not a direct adaptation. The novel holds great meaning for the protagonist, but the story itself is an original fantasy adventure.

Animation Director: Takeshi Honda | Music: Joe Hisaishi

The animation director for this film is Takeshi Honda.

Producer Toshio Suzuki stated that unlike previous films where Miyazaki personally worked on every scene, for this film he focused solely on the storyboards while leaving the key animation fully to Honda. Suzuki said this allowed the film to become “increasingly interesting.”

Honda is a director at Studio Ghibli who has worked on:

– 2008 – Ponyo on the Cliff: His first time working on a Miyazaki film

– 2011 – From Up on Poppy Hill: Key animation

– 2013 – The Wind Rises: Miyazaki personally requested him to work on key animation (the reunion scene at the train station between Jiro and Naoko)

After this film was completed, Miyazaki commented “If I have the chance, I’d like to work closely with him again.”

– 2021 – Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon A Time: Original character design proposals

He is a highly trusted director at Ghibli with years of experience.

It was also announced on July 4th, 2023 that Joe Hisaishi, known for the iconic music across Ghibli films, would be scoring the music.

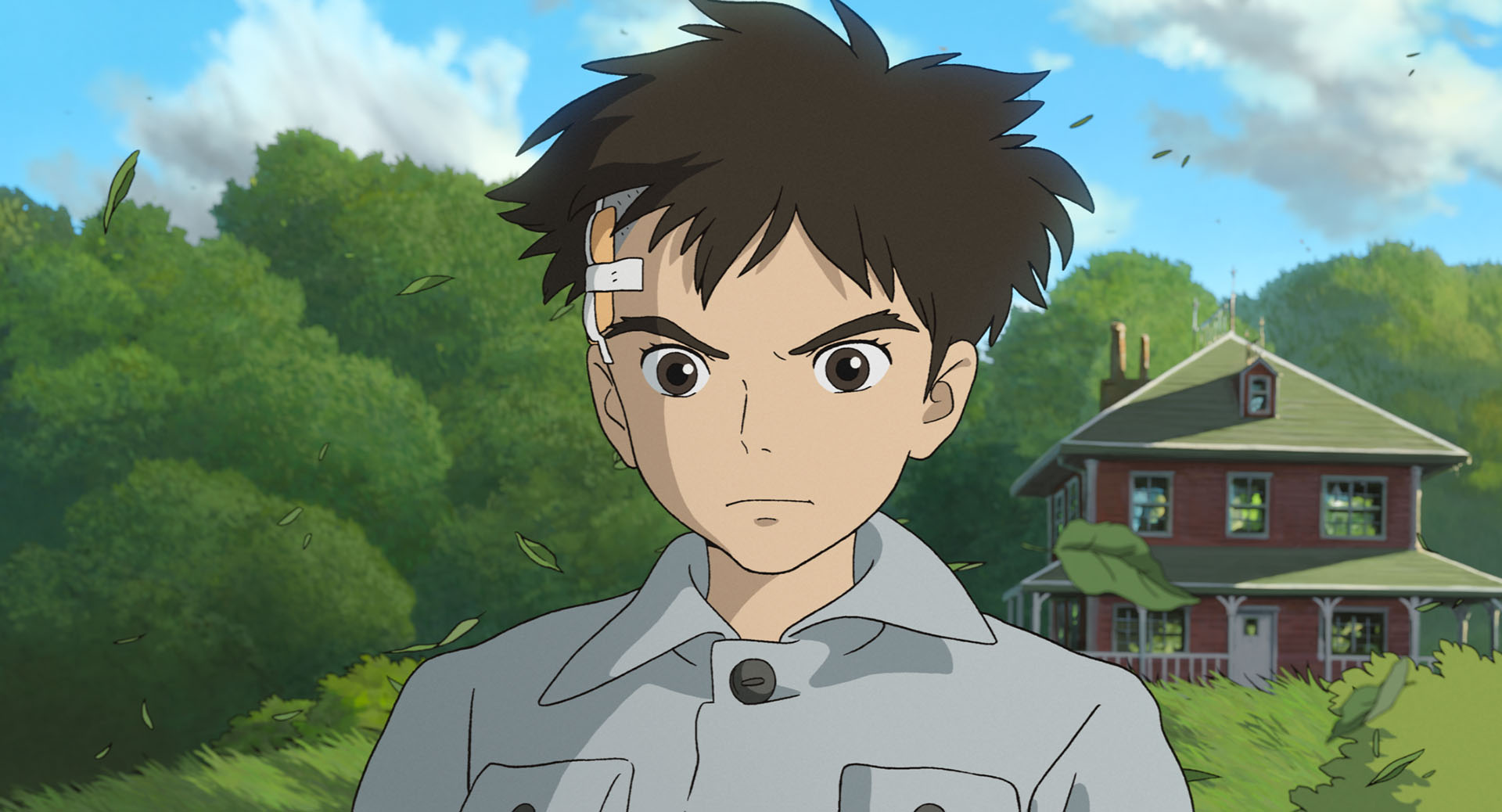

[Act One] An Imprisoned Mother | The Scars of War on Mahito

This act depicts Mahito escaping from war-torn Tokyo to take shelter with relatives.

In just one year from his mother’s death in an air raid to having to evacuate, Mahito is unable to come to terms with losing his mother before he has to start living with a new mother figure.

(A child subject to his father’s circumstances was common during Japan’s patriarchal family system at the time, leaving Mahito powerless)

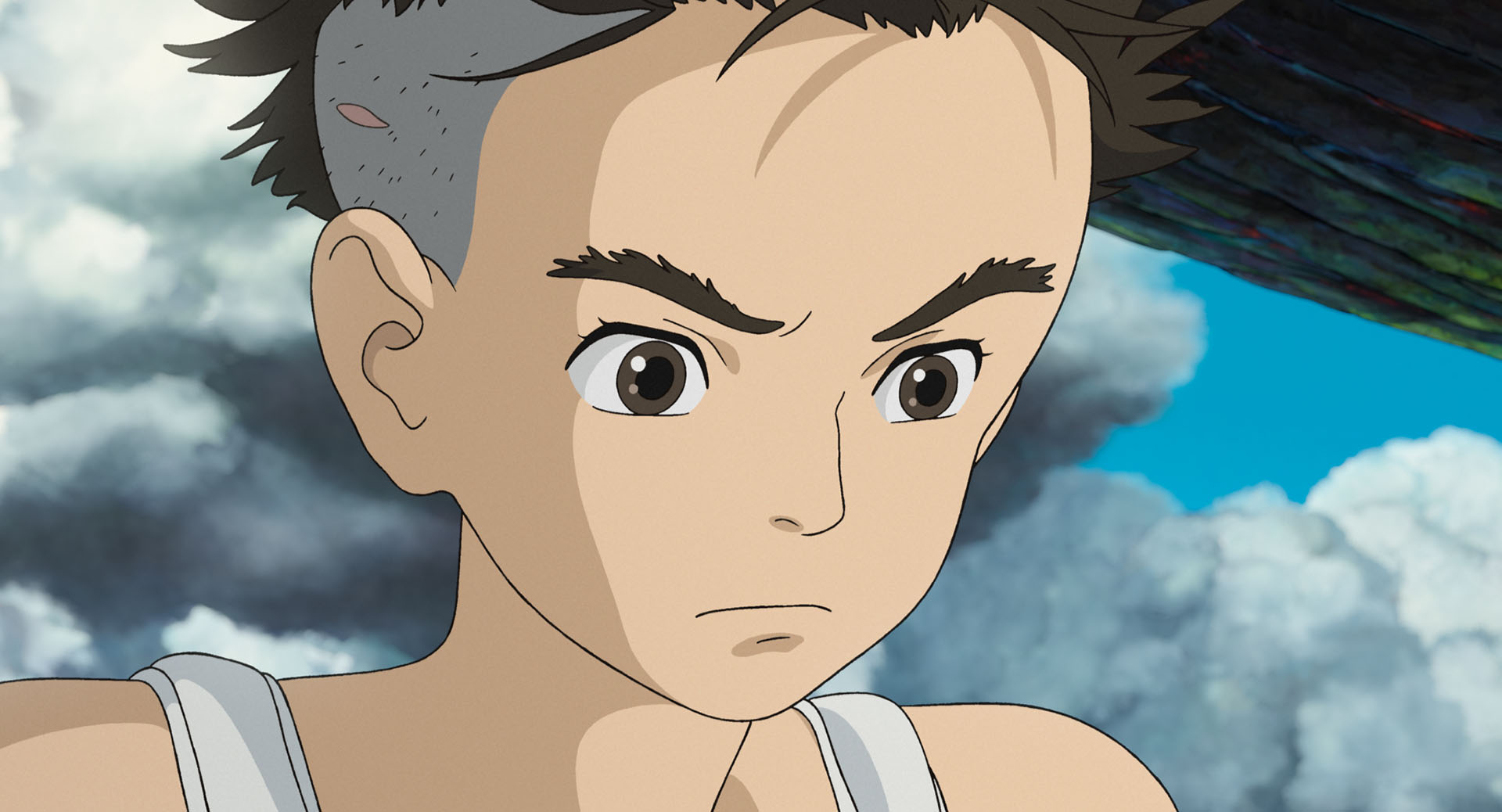

Mahito’s Circumstances | Losing His Mother and Home in the War

The film opens with air raid sirens.

The year is 1944, three years into the Pacific War. During the Tokyo air raids this year, protagonist Mahito loses his mother.

(She perishes when the hospital she’s admitted at burns down)

The scenes depicting this are chillingly terrifying, tragic, and spectacular – unlike anything seen in a Ghibli film before.

The frantic pace and tension are incredible. More than real flames, it’s the portrayed flames that convey a ruthless despair.

The faces and figures of people around Mahito distort and collapse, drawn in a more realistic human manner.

This hellish chaos casts a dark shadow over Mahito’s heart.

I couldn’t save Mother. She burned away.

Mahito: “My mother died in the third year of the war. I moved in the fourth year.”

This “fourth year” refers to the year of the Great Tokyo Air Raid.

□ Great Tokyo Air Raid = March 10th, 1945

The air raids on Tokyo lasted from November 24th, 1944 to August 15th, 1945.

To escape the air raids, Mahito’s father takes him to evacuate to his mother’s hometown.

□ Evacuation = Relocating residents and buildings concentrated in cities to the countryside to minimize damage from air raids, fires, etc.

A One-Sided Reality | His Father Remarries (Pregnancy)

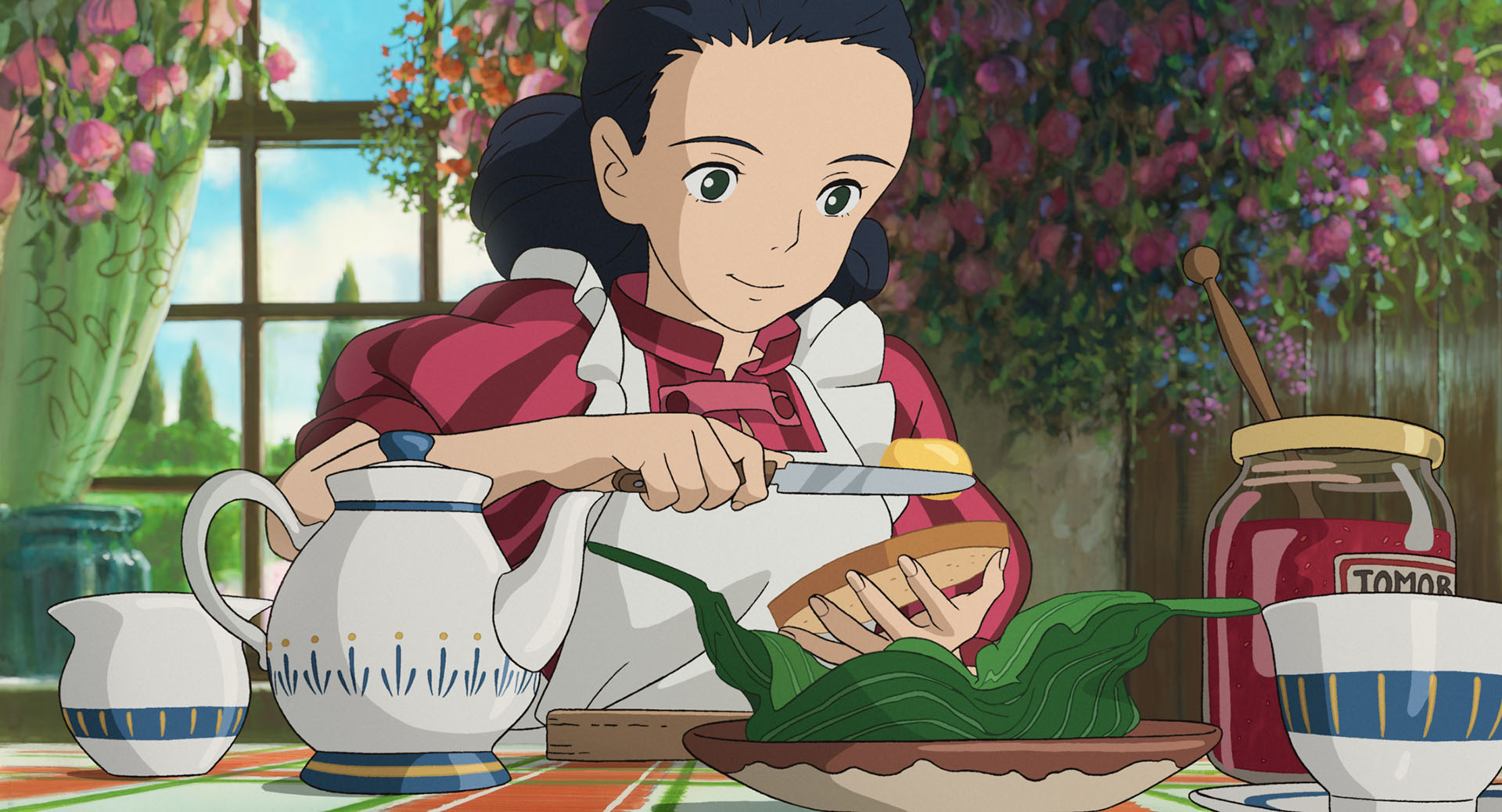

Upon arriving, Mahito is greeted by a woman who looks exactly like his late mother – Natsuko.

“I will be your new mother from today on, Mahito-kun.”

Mahito soon learns that Natsuko is pregnant with his father’s child.

(At first glance, this seems like his father’s infidelity. But during wartime, men remarrying their wife’s sister was common – marriage held the purpose of protecting the household over romance)

Understandably, Mahito has been unable to move on from his mother’s death.

He completely shuts his heart away, barely responding to Natsuko’s kindness.

Encounter with the Heron | Folk depictions of bad luck flying into the house

As Natsuko is giving Mahito a tour of the house, a heron suddenly flies through the room.

Natsuko: “A peeking heron. It’s never flown inside before.”

The meaning behind this scene foreshadows the heron’s later involvement with Mahito. It also incorporates folklore elements relating to Japan’s southern islands (Okinawa, Amami). Lush southern forests and flowers depicted throughout the film back up this “southern island” setting.

Key points regarding southern islands folklore:

– The southern islanders held a distinct perspective on life and death compared to mainland Japan.

– The sea was seen as connecting the mundane world with the spiritual world in a continuous space.

– The boundary line between worlds was believed to exist at the water’s edge, where the mythical realm of Nirai-Kanai was thought to begin.

Southern Island Folk Beliefs:

“When a bird flies into the home”

– It was believed that when a deceased ancestor had a request for their living descendants, a spiritual sign would come from the afterlife. This is known in dialects as “a request from the soul.” Receiving such signs, people in the past would divine their ancestor’s will through the utaki (sacred sites).

In other words, according to traditional southern islanders, the occurrence of a bird suddenly flying into one’s home was seen as an ominous premonition.

And indeed, the heron’s trap for Mahito begins here. The abrupt, foreboding quality of this scene intuitively conveys that “something (likely unpleasant) is going to happen.”

The heron first peeking out from the roof tiles above a shisa statue also represents an ominous presence. Shisa statues protect homes from evil, yet the heron boldly remains perched there, visually communicating a sense of misfortune.

Mahito’s Reality | His “Mother” Trapped in Flames, Mysterious Stone Tower Discovery

Exhausted from his journey, Mahito drifts off to sleep in his new room and dreams of the night his mother died. Importantly, he did not actually witness her death firsthand. Later, the heron taunts Mahito by saying “you didn’t see her corpse.”

Without having seen it himself, the fact of his mother’s death by fire lacks reality for Mahito. More real to him is the sensation that she remains trapped in those flames – he too can’t escape the memory of that inferno. This drives his continual wishing to “save Mother.”

Upon waking, Mahito impulsively steps outside and happens to find a mysterious stone-stacked tower deep in the backyard forest. Though the maid Kiriko pulls him back before he can enter, crucial foreshadowing comes from her dialogue:

Kiriko: “You’ll get drawn in if you go near (the tower).”

Next, Mahito being lonely at his new home and school is depicted.

Mahito’s Loneliness | Accelerated Not By His “Aunt” But His “Father” → Injured Through Malice

[Scene 1] Late at night, Mahito’s father returns and kisses Natsuko at the entryway. Just prior, Mahito’s loneliness was conveyed through his and Natsuko’s shoes sitting distantly apart at the genkan. But the shoes he wants to see there are his Father’s.

– Mahito waits for his father upstairs, only to painfully witness his kiss with Natsuko, accelerating his isolation.

[Scene 2] Mahito commuting by car with his wealthy father

– Flaunting his status thoughtlessly earns Mahito the resentment of peers

His father’s actions critically underlie both these scenes.

Mahito’s Heart:

– The one who should be my ally – Father – instead makes me suffer so much

Thoughts of “it’s Father’s fault” stir up two emotions in Mahito – 1) anger at wanting to make his father worry, and 2) loneliness in craving attention.

To fulfill these, Mahito harms himself by striking his head with a rock, intentionally wounding himself through malice. As intended, his father rushes to Mahito’s side, angrily confronting the school.

Mahito’s Frustration | Knowing But Unable To Take The “Right” Action

As Mahito schemed, his father aggressively pressures the school, even saying Mahito can quit attending. Yet for some reason, Mahito feels no relief. Deep down, he understands he is in the wrong.

At this time, the heron visits Mahito’s window.

Heron: “Mahito, tasukete (save me)! Tasukete!”

But these words are not the heron’s own. Through the heron, Mahito’s mother (trapped in the inferno) cries out.

For reasons not yet known, the heron deliberately provokes Mahito’s wish to “save Mother.” Enraged, Mahito becomes fixated on the heron.

Why does the heron torment Mahito so? The next act reveals the reason.

[Act Two] Rescuing “Mother” (1)

Act two depicts the process of Mohito confronting his own “malice” and acknowledging it through various experiences.

(Specific [scenes] are from “The Provocation of the Blue Heron” to “The Collapse of the Stone Tower.

Since this is a very informative section, [Act two] will be divided into stages from (1) to (3).

In (1), the process of Mahito’s [conversion] through “his father’s teachings” and “his mother’s teachings” is described.

Mahito’s actions (1) Weapons manufacturing|Solutions learned from his “father

Finding his anger with Aosagi, Mahito confronts him with a wooden sword in his hand.

However, he is easily crushed by the blue heron.

Natsuko’s arrow (kaburaya) saves his life.

(But after this, Natsuko falls ill and goes to bed = morning sickness.)

Kaburaya…An arrow that flies while making a sound. Kaburaya…An arrow that flies while making a sound, used as a signal to start the war.

Taking a hint from this, Mahito began to make bows. (The beginning of the battle)

The key point here is that the work is set during wartime.

Mahito’s actions

(1) Stealing cigarettes from Natsuko’s room when he goes to visit her*1.

(2) Gives cigarettes to an old servant man (*2) and teaches him how to sharpen knives (and perhaps even how to make a bow) = how to make weapons.

1 [The scene of the visit] will be described later.

2 Learning weapons from an “old man” instead of a “grandmother (woman)” (perhaps an expression of the patriarchal system of the time).

↓ In other words,

(1) Stealing,

(2) buy weapons in exchange for bribes.

This series of [Mahito’s actions] overlaps with those of his father.

(1) Bribe (donation*) to the school to deal with the aftermath of (Mahito’s false injury).

Fathers who take the initiative to make a donation without hesitation = actions that can be taken as being experienced in bribes.

(2) (This is a guess, but) using the bribed teacher as a weapon, sanction the student who hit him (should be). (Especially if it is wartime)

Mahito’s father is in a profitable war-making business.

Specifically, it is revealed in this [second act] that he is a “fighter jet production plant.

(The windshield part of the cockpit is temporarily placed in the mansion.)

His son, Mahito, also chooses to manufacture weapons as the “first means” to solve [the problem].

In this way, Mahito is going more and more in the wrong direction*,

He gets an unexpected byproduct from this bow-making.

*This means that “the use of force is wrong” in the modern moral sense. In wartime, it is rather “right and honorable” behavior.

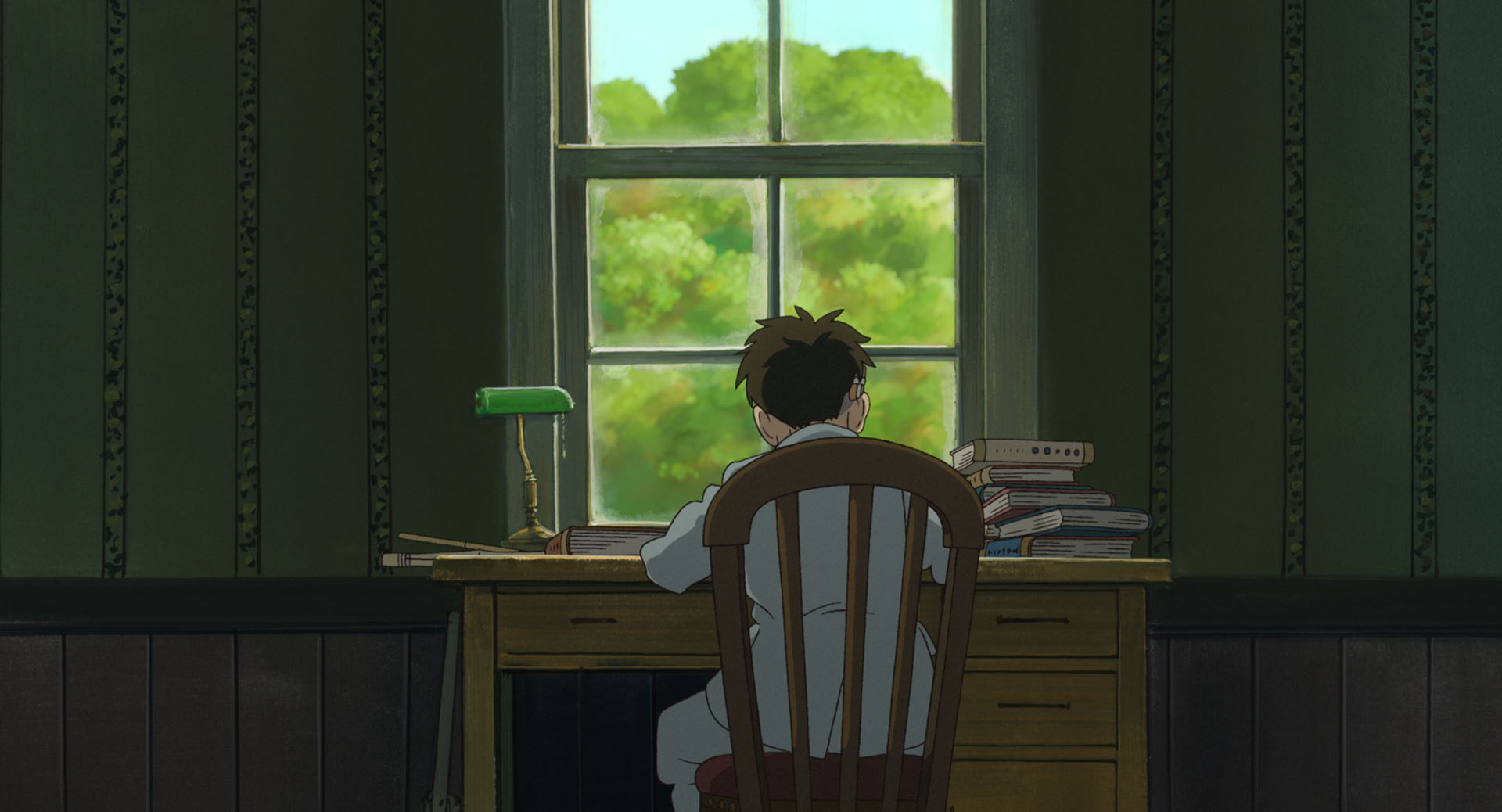

Mahito’s Behavior (2) Reforming Bad Intentions|Solutions Learned from “Mothers” = Genzaburo Yoshino, “How Do You Live?

Through the making of bows and arrows, Masato gained two things.

(1) A blue heron’s wind-cut feather arrow

It has tremendous power.

(2) A gift from my mother = Genzaburo Yoshino’s novel “How Do You Live?(The book collapsed in an avalanche when the arrow pierced the wall and was found in the book. (The book was found in an avalanche of books when an arrow pierced the wall, with the message, “To the grown-up Masato.)

Masato finds “How Do You Live?” and reads it with great enthusiasm.The only thing depicted in this [scene] is that Masato is so impressed that he reads it with tears in his eyes.There is no dialogue.However, we can imagine what he was impressed by when we see what happens next.

Until this point, Manjin has been in a state of unbounded suffering (loneliness).He has been suffering (loneliness) for a long time.

(1) The loss of his mother (even her body was never found)(2) Remarriage of his father(3) Stepmother’s (aunt’s) pregnancy

(4) Living in an evacuation zone where he doesn’t fit in (his father doesn’t understand even though he is lonely)

The pain of not being able to cope (loneliness)

(4) Living in an evacuated house where he doesn’t fit in (his father doesn’t understand him)

*Injury – donation to the school.

→And now he just changed his partner from “father” to “blue heron”.

Masato is beginning to realize that “the current way” may be wrong.Because he is a “human being” who understands “morality”.

In “How Do You Live (Manga Edition),” the following is written.

In “How Do You Live (manga version),” it is written, “What informs us of the true humanity of human beings is the human suffering that only human beings feel, even among the same suffering.

Of all the sufferings, the one that penetrates deepest into our hearts and squeezes out the hardest tears from our eyes is the awareness that we have made an irreparable mistake.” =Guilt.

“I can think of perhaps no other thing more painful than the thought, from the heart of morality, that we have made a mistake.”(Quoted in Magazine House, “Manga: You Are What You Live For,” Genzaburo Yoshino, August 24, 2017)

The heart that feels “suffering” is the one that will lead us to the right path,” Yoshino explains.Through this book, which understands, forgives, and accompanies the “anguish you are currently carrying,” you will be “converted” to the right path.

[Remarks] Hayao Miyazaki’s Experience|The One Thing He Couldn’t Say

Let Her Ride In the documentary film “Princess Mononoke, the following real-life experiences of Hayao Miyazaki are described.

(1) Hayao Miyazaki grew up in a wealthy family.

(2) In order to escape from the war, he gets into his father’s truck.

(3) He sees a father and son shouting, “Please give us a ride! (3) He witnesses a father and son shouting, “Please give us a ride!

(4) Hayao Miyazaki was unable to tell his father to give him a ride.

In the documentary, it is said that this experience inspired the portrayal of a protagonist (Ashitaka in this case) who is able to carry out justice.

The director’s “human suffering” and “sense of morality” have remained unchanged since that time in Mahito, the protagonist of this film, “How Do You Live?

Change in Manato|Going to the stone tower for his aunt (a token of his malice)

Mahito’s “reformation” is depicted through his “behavior toward his aunt,” which begins here.

After reading “A Book from My Mother,” he notices that his aunts are looking for his aunt outside the window.

In fact, while Mahito was making arrows from the feathers of a great blue heron, he saw Natsuko walking into the forest (at that time, no action was taken).

(No action was taken at this time = this happened before he read his mother’s book and [reformed].

After [reforming], Mahito immediately joins the search with a wind-cut feather bow and arrow in his hand.

Ever since the first day he moved into the mansion, Mato has been cold to Natsuko.

Although this reaction is “sympathetic” considering Mato’s feelings, it is unmistakably due to “Mahito’s malicious intent. Mahito intentionally chose this reaction. (He knows Natsuko will be disappointed if he does so. (He knows that if he does this, Natsuko will be disappointed, and it is precisely because of this cunning that Mahito even comes up with the idea of hitting her in the head with a rock.)

In “How Do You Live (manga version),” it is also written: “Admitting one’s mistakes is hard.

In “How Do You Live (manga version),” it is also written: “It is hard to admit one’s mistakes. But there is something admirable about being human in the fact that we feel the pain of our mistakes.

We have the power to make our own decisions. We have the power to make our own decisions, but we also make mistakes. But – we have the power to make our own decisions. So we can recover from our mistakes.”

Following the teachings of book (≒Mother), Mahito shakes off Kiriko’s (one of the Baya) restraint* and proceeds into the stone tower.

*Kiriko understands the horror of the stone tower. (I will discuss this later.)

[Act Two] Rescuing “Mother” 2 | To the Spirit World

Inside the stone tower, Mahito confronts the heron again.

Mahito’s wind-cutting arrow pierces a hole in the heron’s beak, taking away its ability to be a heron and leaving it resembling a small old man.

A voice then calls down from the top floor of the tower telling the heron to “Guide (Mahito).”

* Later revealed as the Great-Uncle – a book lover who locked himself away reading inside the stone tower until he disappeared. Also constructed the tower itself.

Guided by the heron, Mahito and Kiriko sink down through the floor, departing on a journey to the spirit world.

There is so much information covered in the scenes that follow, I will summarize each development separately.

Storyline | Meeting Young Kiriko at the Shore → Setting Off With the Heron

When he comes to, Mahito finds himself alone standing on a beach.

Along that shore sits a gate with “Those who learn of me die (Ware wo manabu mono wa shisu)” inscribed, graves faintly visible beyond.

A mass of pelicans then swarms toward Mahito from the beach.

Swept along, Mahito opens the gate, only to be rescued by a woman who rides over on a boat.

Despite looking vibrant and youthful, this woman wears the same clothes as Kiriko, who entered this world with Mahito.

(An explanation for Kiriko’s youth follows later. For clarity she is noted as “Young Kiriko” hereafter)

Having been saved, Mahito fishes with Young Kiriko, then guts the catch, but faints buried under fish entrails and gets carried back to her home.

That night, Mahito witnesses small, round, white creatures (warawara) flying up into the sky.

Young Kiriko: “Lately they couldn’t fly at all. But after getting their bellies full, they finally can.”

* Earlier, dialogue notes the fish guts nourish the warawara

But descending pelicans voraciously devour them one after another.

The warawara’s crisis is rescued by Himi, who also wields fire like Kiriko, sweeping up warawara in her attack yet fending off the pelicans.

(Seeing warawara caught in the crossfire, only Mahito panics. Young Kiriko calmly says “Thank you Himi-sama!”)

Mahito then speaks with an injured pelican unable to fly after Himi’s skirmish.

Lamenting the hardship of life here as it dies, Mahito buries its body.

The next morning after sleeping surrounded by the maid dolls, Mahito sets off from Young Kiriko’s home, entrusted with a protective charm – Kiriko’s doll.

He then heads toward the parrot blacksmith guided by the heron, aiming to save Natsuko.

Meaning of the “Shore” | Between Life and Death

As described in the folkloric depiction of the heron flying into the home, I will elaborate more on the “shore” here.

Key folkloric points regarding the shore:

[Shore] * Particularly in southern islands (Okinawa, Amami)

– Seen as the boundary between the mundane world (= this world) and spirit world (= other world)

– “Birthing huts” and “burial grounds (graves)” were once close to the sea

(Believed closest to the ancestral spirits’ dwelling in Nirai-Kanai beyond the sea)

– For southern islanders, “human birth” = “rebirth of ancestral spirit”

Therefore, the shore = the intersection of “life” and “death”

– Where tides ebb and flow daily, mornings leave and evenings visit = a place of repetition

(Source: ‘Ethnography of the Shore’ by Kenichi Tanikawa, Nihon Minzoku Bunka Shiryō Shūsei Vol. 5)

It can be inferred that the “shore” Mahito arrives at represents a world “between life and death.”

Meaning of “Those who learn of me die” | Grave (Iwakura) of Malice

The meaning behind “Those who learn of me die (Ware wo manabu mono wa shisu)” remains unclear in this scene. But later when Mahito visits Natsuko’s birthing hut and faces his Great Uncle, hints arise:

(In response to the Great Uncle calling it “building blocks”)

Mahito: “That isn’t wood, it’s stone. The same as gravestones, stones of malice.”

This ties “grave” to “malice.”

Interpreting this rule – “Ware” (grave, or the stones comprising it) = “Malice”

In other words, “Those who learn of malice will die.”

Taking it further, “Those who learn of malice” = “Those who live by malice”

One cannot live (shisu = die) without abandoning malice.

* And so Mahito wants to save Natsuko (atone for his malice) and Coppé in the novel ‘The Boy and the Heron’ also struggles with anguish.

I interpret an underlying message here (a moral lesson in living as human).

This coastal “grave (resembling a cave)” also evokes Iwakura.

[Iwakura]

– Iwakura are sacred stones and rock formations worshipped in ancient Shinto. The rocks themselves are the object of worship. (Source: Iwakura on Wikipedia)

– Stones considered to house gods. In ancient animism, nature itself was revered and gods were believed to inhabit mountains, trees, rocks and so on. Particularly sacred stones (rocks) became objects of worship. (Source: Kotobank)

Iwakura also appear in ‘Princess Mononoke’ – Eboshi’s cottage, the large boulder in Shishi-gami’s pool, the wolves’ den.

Viewing it as an Iwakura, it can be interpreted as “stones housing the god of malice.”

Yamato Takeru Legend ‘Fire Attack, White Heron’ | What the “White Heron” Symbolizes

When saving Mahito from the attacking pelicans, Young Kiriko uses a flaming whip, wielded in a distinctly Japanese mythological style.

[Young Kiriko’s Actions]

1. Mowing grass with the whip

2. Creating a barrier for rescued Mahito (burning surrounding grass)

An old Japanese myth exists about ‘fire attacks.’

(Called Yamato Takeru no Mikoto in ‘Kojiki,’ Yamato Takerunomikoto in ‘Nihon Shoki.’ Simply noted as Yamato Takeru here)

The legend goes:

‘Fire Attack Legend’

1. While heading to defeat a deity, Yamato Takeru gets caught in a fire attack on the plains.

2. He wards off the approaching inferno by fighting fire with fire.

* In ‘Kojiki,’ he “mows down grass with Kusanagi sword and drives back fire with counterfire.”

Like Yamato Takeru, Young Kiriko repels the enemy (malice) using fire.

(Yamato Takeru faces ‘fire attacks’ due to underhanded schemes = malice in the first place)

Moreover, the entire work incorporates the ‘White Heron Legend,’ another Yamato Takeru story:

‘White Heron Legend’

1. Slain by a mountain deity, Yamato Takeru dies.

2. At his funeral, Yamato Takeru’s spirit leaves flying away transformed as a white heron.

* ‘Kojiki’ names the deity “Shiroi Ooi ≒ Ototachimainu,” ‘Nihon Shoki’ calls it “Giant Snake ≒ Tatarigami”

* ‘Kojiki’: “Yahiro Shiro Chidori,” ‘Nihon Shoki’: “White Heron”

This ‘White Heron Legend’ relates to the extensive appearance of birds throughout the film.

Key folkloric points regarding white herons:

[White Heron]

* Refers more to shiratori than actual swans

– Ancient people revered the pure white migratory animals (white birds) annually visiting

Their awe inspired imaginings like Yamato Takeru’s ‘White Heron Legend’ –

His dead spirit (slain emperor) leaves “flying away transformed as a white heron.” Interpreting “birds’ migration” = “souls’ departure”

→ Conclusion: “White herons carry departed souls”

(“White heron” = bird from Tokoyo transporting souls. Recognized as one kind of marebito)

□ Tokoyo = Nirai-Kanai, undersea, Mount Horai, all indicating lands of immortality (especially in southern islands = Okinawa, Amami)

* ‘Shirayuri Bushi’ folk songs from Amami Island portray white herons playing similar roles

(Source: ‘The White Heron – Cultural History of Objects and Humans’ by Masaharu Akabane)

While the film features herons and pelicans, the key point is not differentiation of species but their shared whiteness.

(Conversely, the specific bird doesn’t matter as long as it’s white. The white boar Ototachimainu holds significance for that quality over its exact form in ‘Princess Mononoke’)

“White birds” traverse between this world and the next.

(The historical understanding – modern science has revealed actual migration habits)

Thus in this “shore” world “between life and death,” pelicans exist and the heron functions as a character crossing “this world and the next.”

True Identity of the Warawara | Hints in Kiriko’s Dialogue

Cute, round, white creatures called warawara appear in the film. Currently I theorize they represent “life just before being born into this world.”

* Babies are also “round, cute creatures”

Boarding Young Kiriko’s boat from the shore, Mahito hears her say:

Young Kiriko: “There are more dead than living people here.”

The key hint comes from the film’s setting in wartime Japan.

Mahito evacuated in 1945, just after the devastating March Tokyo air raids.

A fleet of distant sailing ships and hand-rowed boats are depicted along the sea.

On Mahito’s first day commuting to his new school, his father remarks:

“I figured Saipan would last a year, but oh well, its fall has brought good fortune.”

[Battle of Saipan]

June 15th – July 9th, 1944

– Battle between American and Japanese forces on Saipan island

– The Japanese army was completely annihilated

Considering this backdrop, the subtly shown sailing ships and hand-rowed boats likely represent fallen soldiers.

Rewording Young Kiriko’s “more dead than living people” from the perspective of “this world” –

“More people dying than being born.”

As described before, the shore signifies the “space between life and death.”

The warawara that rise into the sky from there represent beings trying to “come into life” in the real world.

Tenderly watching over the warawara finally able to fly, Young Kiriko seems an extremely maternal, midwife-like character.

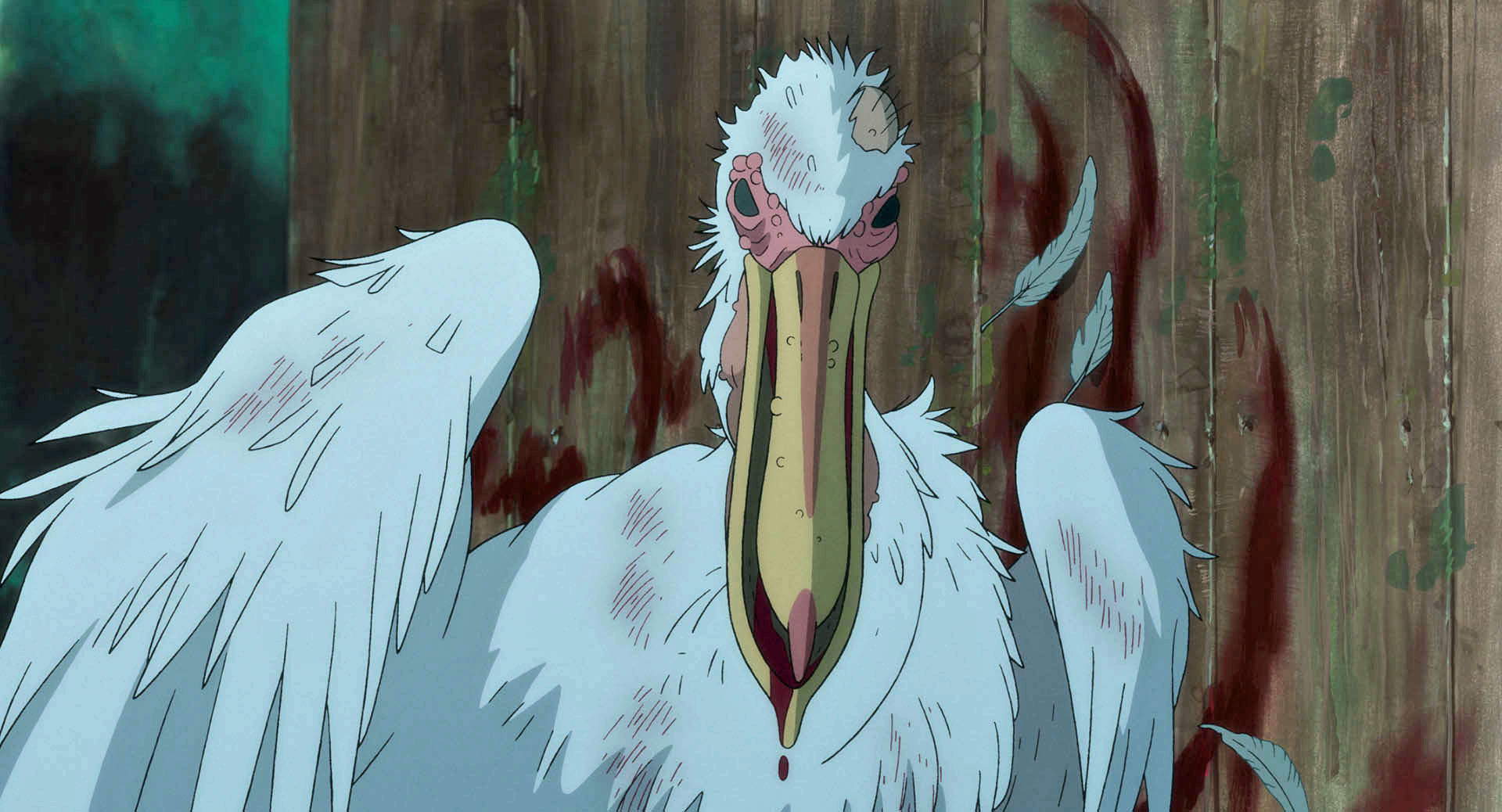

True Identity of the Pelicans | Fate of Those Who Pile Up “Petty Malice”

Scene at the Gate of the Grave:

The pelican flock stealthily encroaches then swarms Mahito from behind,

pushing him toward the grave chanting “Eat… Eat…”

As discussed earlier, I believe the “grave” is where “malice” sleeps.

(See: Meaning of “Those who learn of me die” | Grave (Iwakura) of Malice)

Based on this, the pelicans’ actions could be interpreted as leading Mahito into “malice.”

Next in the night scene with the warawara:

I theorized the warawara represent beings trying to come into this world.

(See: True Identity of the Warawara | Hints in Kiriko’s Dialogue)

Framing the pelicans as “hunters” gives the following schema:

Warawara: Float up into the air, moving toward being born into “this world”

= Existence trying to step into the “next world”

↑

Pelicans: Successively swoop down devouring one after another

= Beings that simply obstruct for no reason through force of numbers

My basis for writing “for no reason” relates to the following dialogue from the dying pelican Mahito discovers:

Old Pelican: “With too little food, I had no choice but to live by eating warawara.”

The pelicans aren’t eating warawara out of desire (“active motive”).

Simply nothing else to eat, so they’re “just eating them to survive (passive motive).”

(The warawara as innocent beings merely trying to fly become victims of this irrationality)

In a word, the “pelicans'” true identity is “petty malice.”

Take bullying for instance.

One child singles out a target to harass. For no reason, other children pile on until the whole class gangs up on one victim.

(By then, no one even remembers who started it or why they’re bullying in the first place)

“If they’re doing it, I guess it’s okay if I do it a little too” –

that kind of “petty malice” clustering together forms the “flock of pelicans.”

The more this flock increases in number, the more self-righteous and reassured in their persecution they feel.

(Hence swarming Mahito chanting “Eat… Eat…” with no purpose, trying to make him one of the “petty malice” gang)

Old Pelican: “My wing’s busted. Just kill me why don’t you.”

Cast out from the flock, the old pelican makes excuses until death comes.

“We can’t escape from this ‘hell’.”

“I’ve tried flying high to get out of here too, but always end up back in the same place.”

“Most comrades have even forgotten how to fly.”

This is the fate met by those who persist alongside clusters of “petty malice.”

(Flocked together, they become unable to fly despite having wings)

Symbolizing “those who’ve forgotten how to reform.”

As white birds, pelicans possess the same capacity as herons based on in-world rules and folklore to traverse “this world” and the “next” anytime.

Yet unlike the heron, pelicans render themselves unable to “fly.”

Why? – Due to remaining with the flock completely unaware of their own “malice.”

(After getting its beak hole patched, the heron gradually assists Mahito more, finally becoming friends = self-reflecting and reforming on its own)

To me, “Those who learn of me die (Ware wo manabu mono wa shisu)” directly indicates this kind of state.

* “Those who learn of Ware (grave)” → “Those who learn of Malice” → “Those who live dependent on Malice”

[Act Two] Rescuing “Mother” 3 | Mahito’s Answer

Act Two Part 3 depicts Mahito meeting Himi and solidifying his resolve, then reuniting with Natsuko to give the Great Uncle his answer.

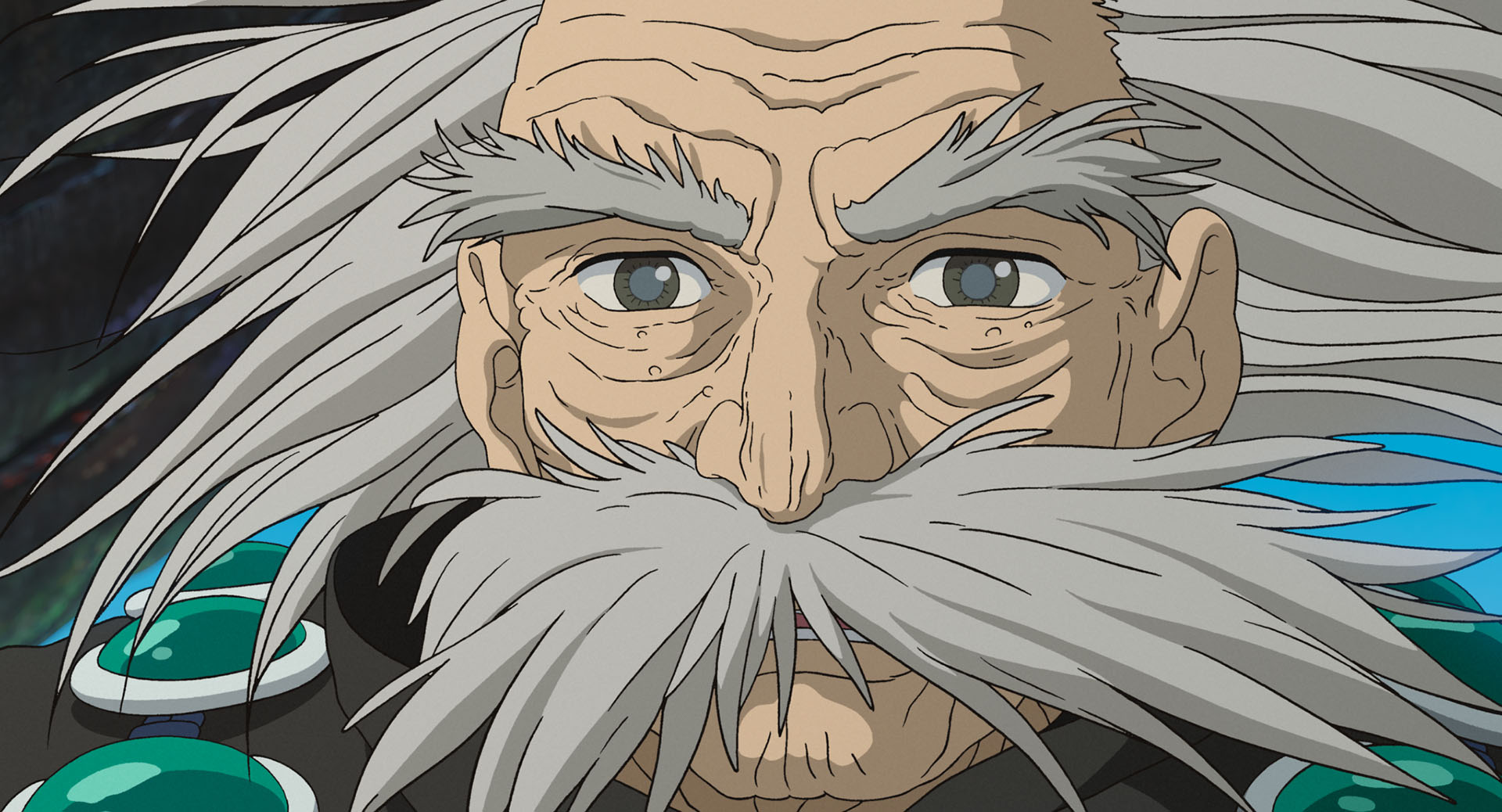

Mahito Meets Himi | Backstory on the “Stone Tower”

Tropical plants appear along Mahito’s path with the heron, backing my tie to Okinawan folklore. Birou leaves (like sakaki plants carrying folk meaning in Honshu) also appear around the Great Uncle later.

Arriving at the parrot smithy searching for Natsuko, Mahito sneaks inside using the heron as a decoy. But many parrots still remain, soon leaving him in dire straits again – facing getting eaten.

Himi rescues Mahito from this crisis. Their conversation reveals “Himi is (Mahito’s) mother’s younger sister,” informing the audience of their familial tie.

Meanwhile in reality, Mahito and Natsuko’s disappearances prompt a search by his father and the maids.

(Though he solves everything with money, his father’s love for Mahito and Natsuko is unchanged)

Here, one maid conveys the stone tower’s backstory:

[History of the Stone Tower]

1. Reason for construction

– One day it suddenly fell from the sky

→ To protect it, the Great Uncle built the stone tower. Many died during construction

2. The Great Uncle’s disappearance

– An avid reader, he holed himself up inside, eventually vanishing

3. Sealing the stone tower

– After his disappearance it was deemed dangerous and the entrance sealed

4. Himi (Mahito’s mother) vanishing

– Somehow the entrance opened and young Himi went inside

5. Himi returns

– After a year she came back looking exactly as when she disappeared

Hearing this, Mahito’s father heads toward the stone tower with the maids.

Mahito’s Resolve | To Return Home Together with Natsuko

Sheltered at Himi’s home, Mahito delights as she serves him jam toast – it’s exactly like his late mother’s.

Knowing Natsuko’s location, their path there conveys Mahito solidifying his resolve.

The stone tower interior contains an endless hallway lined with numbered doors.

Pointing to one (Door #132), Himi tells Mahito “You can return from here.”

Sure enough, beyond that doorway connects back to reality in the other world.

(While gripping the knob they can linger in the “connecting world”)

Exploiting this, Himi and Mahito dodge the pursuing parrots.

But Mahito chooses not to return to reality there because he hasn’t achieved his goal of bringing Natsuko back.

He won’t go back without Natsuko – displaying his resolve.

The Director’s Intent | Spotting Toyotama-hime Mythology in the Birthing Hut

Guided by Himi, Mahito finally arrives at the birthing hut where Natsuko waits. But Himi halts, saying “I won’t go in. I’ll be out here.”

The key point here involves Japanese mythology about “birthing huts” – prime examples of taboos in folklore.

□ Birthing Hut (ubuya)

– Like mourning huts and menstrual huts, a small building for socially isolating the ritually unclean

– Hut for isolating women giving birth

(Either solely a living space for post-birth mother seclusion, or doubling as the actual birthing locale)

Well before the advent of hospitals, designated birthing spaces related more to beliefs shunning “blood impurity” than privacy concerns.

(See my ‘Princess Mononoke’ analysis for details on folklore regarding “impurity” and “gazing”)

Of the Japanese myths featuring birthing huts, this work ties strongly to Toyotama-hime’s story.

□ Toyotama-hime (Toyotama-bime in ‘Kojiki,’ Toyotama-hime in ‘Nihon Shoki’)

– Goddess appearing in Japanese mythology, known as grandmother on father’s side and aunt on mother’s side to first emperor Jinmu

(Reference: Toyotama-hime on Kotobank)

Toyotama-hime Myth:

1. Daughter of sea god Watatsumi, Toyotama-hime marries Hoori-no-mikoto when he visits the sea god’s palace.

2. She goes ashore to give birth, secluding herself in a coastal birthing hut.

Hoori-no-mikoto peeks inside – violating this “taboo.”

3. Toyotama-hime writhed suffering inside the hut in a crocodile form – appearing frightful.

4. Furious (ashamed) over being seen, she leaves the baby behind to return to the undersea realm.

Later when the heron says “You violated the taboo (What taboo? Mahito asks). I’m talking about taboos!” – this myth forms the basis.

It also drives Natsuko’s rage soon after.

In fact, Toyotama-hime’s myth continues:

[What Follows in Toyotama-hime’s Myth]

1. After abandoning her baby (Ugaya-fukiaezu-no-mikoto) on the shore to rejoin the land of the dead,

her younger sister Tamayori-hime comes in her stead from the undersea realm to raise the child.

* Ugaya-fukiaezu-no-mikoto = “born before the birthing hut was finished”

2. Tamayori-hime raises the baby

→ From the baby’s view, Tamayori-hime = Aunt

3. Once grown, the child takes Tamayori-hime as his wife, becoming Jinmu’s (first emperor) father

* Common mythic trope of ancestral imperial family members engaging in incest

Paralleling this myth, Himi (Mahito’s mother) leaves her child then dies, with her sister Natsuko (Mahito’s aunt) stepping in to fill the maternal role.

The intentionality of these “birthing hut” and “sister” motifs by Director Miyazaki is apparent.

[Anecdote] Another Myth From the Kojiki & Nihon Shoki | Why So Much “Fire” Imagery

Besides Toyotama-hime’s story, another birthing hut myth exists – the Konohanasakuya-hime myth:

[Konohanasakuya-hime Myth]

1. Mountain god’s daughter Konohanasakuya-hime bears child with Ninigi-no-mikoto (Amaterasu’s grandson)

2. He doubts the baby’s paternity since she became pregnant in just one night

3. To clear suspicion, stating “If truly your child, it will be safely born,” she sets fire to her own birthing hut

4. Gives successful birth to the brothers*

* One later weds Toyotama-hime, becoming her husband Hoori-no-mikoto

This myth conveys the formidable strength of life-giving mothers – ancient people likely felt a sense of awe about the agony of childbirth.

As described later, in the finale scene of Himi and Mahito’s parting:

Himi: “(Mahito pleads for her to not return home to die again in the air raids, but she responds) Of course I’m going back! Giving birth to you will be wonderful!”

Through this line, Director Miyazaki imbues notions of feminine power.

Himi’s fiery abilities become the means to dramatize this as action – her own “burning away” (fiery death) also intentional.

* As an aside, Hoori-no-mikoto’s name means “born when the birthing hut flames died down.”

The Reason for Natsuko’s Rejection of mahito at the Maternity Hut

When mahito enters (≒peeks into) the maternity hut, he faces intense rejection from Natsuko.

Natsuko: “I hate you so much!”

One reason behind this furious reaction is that it follows the “taboo of the maternity hut = the myth of Toyotama-hime” mentioned earlier. It’s an inevitable result of that.

* White paper streamers (shide) hang around because it’s a “sacred place.”

□ Shide… Although when attached to tamagushi, haraegushi, and gohei it has the meaning of a ritual implement to ward off evil, when hung from a shimenawa to delimit a sacred area or ritual site it serves as a mark indicating a holy precinct.

Another reason lies in Natsuko’s character.

Looking back at the story so far from Natsuko’s perspective:

Natsuko’s Story

1. Her sister Himiko dies in an air raid while hospitalized.

2. To protect the household (leave descendants), she marries Himiko’s brother-in-law (mahito’s father).

↑ In the first part, like mahito, Natsuko has a “unilateral reality” forced upon her.

3. She becomes an aunt (and of course ends up being saddled with caring for him).

4. But no matter how she tries to approach him, her nephew remains cold.

On top of that, Natsuko is under great stress from her impending childbirth (and the accompanying anxiety).

(That’s why she goes to the stone tower. I’ll explain that later.)

The line “I hate you so much!” encapsulates all the stress that has built up. It is Natsuko’s true feelings.

ex. In Hayao Miyazaki’s Grave of the Fireflies, the “auntie” character exposes her stress toward Seita and Setsuko from the very beginning.

[Side Note] Why the Inside of the Stone Tower Feels “Prickly”

When mahito touches the stone wall on his way to the maternity hut, he gets prickly zapped.

The reason this attack is described as “prickly” is:

Inside Natsuko’s maternity hut, there are “paper streamers (shide)” encircling it to form a spiritual border. (See: The reason for Natsuko’s rejection of mahito at the maternity hut)

These shide streamers have the following rules:

Shide – Paper folded in a special way then torn.

↑ Made in a form reminiscent of lightning bolts to dispel evil things. Lightning and thunder → good harvest → something welcomed in olden times.

That’s why when mahito touches the stone wall (the border), he gets “prickly zapped.”

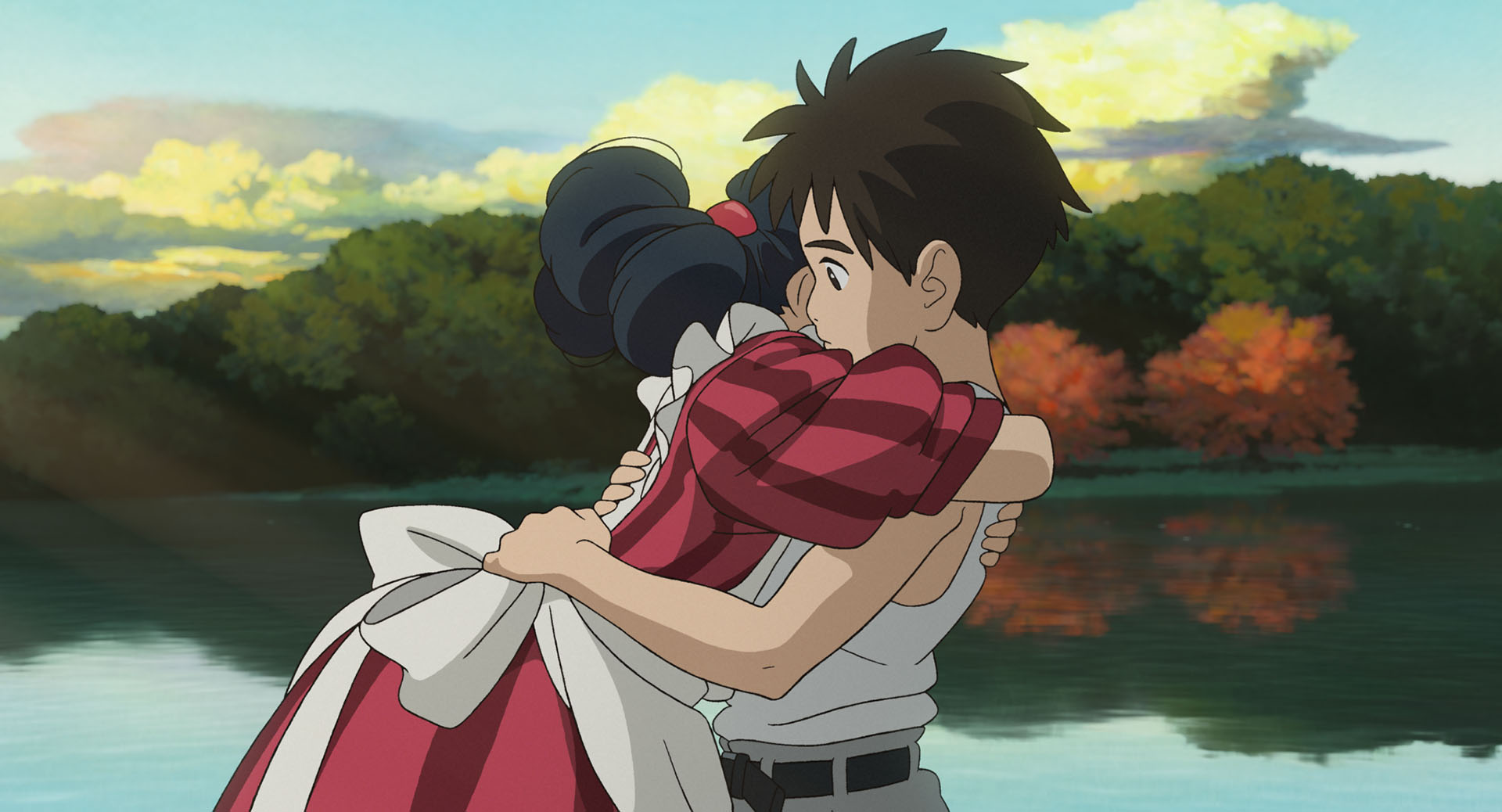

mahito’s Growth – Why He Calls Natsuko “Mother”: Connecting “Malice” with “Sincerity”

After running up against Natsuko’s true feelings, mahito’s feelings also come pouring out.

mahito: “Auntie! …… Natsuko, Mother!”

I’d like you to recall the hospital visit scene depicted in the first act.

When prompted by one of the old women “We were very worried about you,” mahito reluctantly goes to visit Natsuko (who is bedridden with morning sickness).

Natsuko then strokes mahito’s wound (the one she inflicted on him out of malice) and says

“I’m so sorry, I’ve done my sister wrong…”

and laments.

** Here it’s made clear Natsuko is the younger sister of mahito’s mother.

To Natsuko, mahito is a source of stress but also a memento of her sister Himiko.

mahito’s heart wavers at Natsuko’s actions.

(No matter whether there was malice behind the wound, Natsuko would lament over it just the same)

mahito’s Feelings

Feeling regret over doing something bad = Remorse (unbearable guilt)

1. I made Natsuko suffer by inflicting this wound out of my own malice.

2. All this time Natsuko was worried about me, yet I kept deliberately acting cold toward her.

By this point in the maternity hut scene mahito is already aware that he has returned Natsuko’s “sincerity” with “malice.”

(His heart changed after reading his mother’s parting words in “How Will You Live?” That’s why he voluntarily heads to the stone tower and even enters Natsuko’s maternity hut)

In response to Natsuko’s true feelings “I hate you so much!”,

mahito calls her “Mother!” as a way of finally returning the “sincerity” he has owed her all this time.

(Not that he has accepted her as his mother, but that he is resolved to accept her as his mother. This is his courtesy toward Natsuko and his fledging from his actual mother – Himiko.)

The Uncle’s Objective – Jungian Dream Analysis

After being driven out of the maternity hut’s spiritual border (the aforementioned shide), mahito and Himiko both faint.

They are then taken prisoner by the tanuki that came chasing after them.

While unconscious, mahito meets his ※Great Uncle in a dream.

This reveals the【Great Uncle’s Objective】.

↑※ Compared to other schools, Jungian psychology places greater emphasis on dream analysis in psychotherapy. The fact that they deliberately have a conversation through a dream also backs up my later interpretation【Consideration】that the Great Uncle = Jung the psychologist, given that “add one block every three days” based on the “13 blocks.”

Great Uncle’s Objective

– By being the lord of the stone tower, maintain the balance of the world.

– The balance is maintained by “blocks”.

↑ Only my descendants can inherit this job, so I want mahito to take over.

* To convey this objective, the Great Uncle had mahito guided (and ultimately provoked outside) by the blue heron.

But mahito declines, saying “Those aren’t ‘trees,’ they’re ‘stones.’ Stones the same as gravestones full of ‘malice.’”

The Fight Over the “Stone Tower” – The Great Uncle Who Wants a Successor vs. The Tanuki Lord Who Wants Control

When mahito wakes from his dream he is in the tanuki’s kitchen.

Just as he is about to get eaten, mahito is saved by the blue heron’s quick wit.

This is where the director’s message appears, referencing the myth of Toyotama-hime I touched on earlier regarding the maternity hut:

Blue Heron: “You violated a taboo.” (When mahito asks what taboo, he replies) “A taboo!”

Because of violating this taboo, Himiko becomes a bargaining chip for the tanuki (wanting control over the “Stone Tower”).

** I will explain more about the tanuki later.

The Collapse of the “Stone Tower” and mahito’s Decision – Confessing His Own “Malice”

Himi, who has awakened under the Great Uncle, goes to fetch mahito.

Guided by her, mahito is reunited with his Great Uncle.

(On the way, mahito passes through the Four Seasons Garden. See “Add One Every Three Days” – Meaning of the Time Differential via Spiriting Away = Inside and Outside the Tower for more details.)

The Great Uncle once more asks mahito to inherit the job of protecting the “Stone Tower.”

Great Uncle’s Request

– 13 blocks = Maintaining the balance of the world.

↑ These are the only stones not yet stained by malice. Add one block every three days to build mahito’s tower, he says.

** Please refer to 【Consideration】”Add One of the 13 Blocks Every Three Days” = Great Uncle as Psychologist Carl Jung for more on this.

But mahito flatly declines his uncle’s request.

mahito: “This wound (on his own head) is proof of my malice. I won’t touch those stones (the ones untainted by malice). I will return to the world with Mother Natsuko.”

↑ To this the Great Uncle replies, “Return to a world of killing each other and taking from each other? It will soon become a sea of flames.”

I currently speculate he is referring to the trend of “Manchurian Incident ※ → Sino-Japanese War (and then Pacific War)”.

※ Manchurian Incident = 1931. Fits with the Great Uncle entering the “Stone Tower” 13 years prior. (See: “13 blocks” = “The 13 years since the Great Uncle disappeared”)

Despite being laconic up to now, in this scene mahito finally confesses his own “malice”.

And then the Tanuki Lord bursts in and the collapse of the “Stone Tower” begins.

[Act Three] Parting from “Mother” and “Return”

Act three depicts mahito parting from Himiko, his “mother,” and returning with Natsuko.

mahito’s Parting – His “Mother” Himiko

Inside the crumbling tower, with the blue heron’s help mahito heads down a corridor lined with exit doors, together with Himiko.

(Natsuko also joins them, aided by the young Kirico)

To return to their respective worlds, mahito and Himiko each grasp separate doors.

Himiko: (as they part) “I’m going to become mahito’s mother.”

mahito: “But if you do, you’ll die in that hospital fire.”

Himiko: “I don’t mind fire. And isn’t it wonderful I get to give birth to mahito?”

mahito: “You can’t. You have to live.”

Himiko: “You’re a good kid.”

The “loss of his mother in a fire” was the triggering event for mahito’s story in this work.

Over the course of the story beginning with the opening act, mahito’s issue develops as follows:

mahito’s Issue

1. His mother (Himiko) trapped in the flames – He did not see her body, so cannot accept her death

↓ Evacuation

2. Rescuing “Mother” (Himiko) – Prodded by the blue heron to “Save her!”

↓ Deeply impressed by How Will You Live, realizes his own “malice” (repents)

3. Rescuing Natsuko – Natsuko disappears into the “Stone Tower”

↓ Meets young Kirico, cooperates with blue heron and Himiko

4. Rescuing “Mother” (Natsuko) – Calls her “Mother Natsuko” at maternity hut = connecting malice

・ Calling her “Mother” saves Natsuko (stepmother)

↓ Collapse of the “Stone Tower”

5. Parting from “Mother” (Himiko) – Himiko returns to give birth to mahito

・ mahito accepts Himiko’s death (that’s why he warns “you’ll die”)

mahito certainly harbored “malice.”

(He still does. The lingering wound on his head is “proof of malice.”)

But on the other hand, mahito also has a sense of “wanting to save his mother.”

Himiko: “I don’t mind fire. And isn’t it wonderful I get to give birth to mahito?”

→ For Himiko, giving birth holds more value than dying.

→ The “fire” is a metaphor for the mother’s strength. (See: [Side Note] Another Take on the Kojiki – Why Fire Imagery is Used So Often)

Himiko: “You’re a good kid.”

→ Accepting mahito together with his malice.

These two lines from Himiko resolve all of mahito’s issues up to this point.

For mahito, his mother’s “unreasonable death” was inevitable for Himiko to give birth to him.

And all of mahito’s “good points” as well as “bad points” – Himiko recognizes him as a “good kid.”

Through this, mahito comes to accept both “his mother’s death” and his own “malice.”

Himiko also calls out to Natsuko (joined by young Kirico):

Himiko: (to sister Natsuko) “Give birth to a nice baby.”

Obviously Himiko doesn’t know the father’s identity.

But Natsuko does.

(At the maternity hut, Natsuko already realized Himiko was her sister as a child)

For Natsuko, those words “give birth to a nice baby” represent forgiveness (for remarrying her sister’s husband) as well as encouragement toward childbirth and her new life.

Hearing it from her sister Himiko saves Natsuko as well. (She can return to her original world)

mahito’s Return 1 – His “Mother” Natsuko

mahito’s original purpose upon evacuating was to “rescue Mother (Himiko).”

But to give birth to mahito, Himiko returns to the past instead of mahito.

In other words, mahito is unable to achieve his original purpose and meets his story’s conclusion.

But looked at differently, in a sense this conclusion does accomplish his purpose.

Because mahito returns after rescuing “Mother (Natsuko).”

mahito is saved by Himiko (his mother), and saves Natsuko (his mother).

This kind of storytelling is another one of the appeals found in Fireflies: How Will You Live.

mahito’s Return 2 – Why He Brings Back “Stones of Malice” = Empathy Toward the Pelicans

Escaping the crumbling Stone Tower along with mahito’s group are the tanuki and pelicans as well.

mahito asks the blue heron, “What about the pelicans?”

In my earlier Pelicans’ True Identity – The Fate of Those Who Harbor “Little Malices”, I interpreted:

Pelicans’ True Identity = “Little Malices”

– Despite having wings, they can no longer fly (unable to escape) – The result of continually immersing themselves among groups of “little malices.”

↑ “Unable to fly” = A state of “having forgotten how to repent”

Based on this, to mahito, the “pelicans” represent “what I might have become.”

(In other words, “not someone else’s problem” = he feels empathy toward them)

That’s why mahito worries over the pelicans and feels relief when the blue heron tells him they got out.

I believe this is also why mahito takes the “stones” with him.

As described earlier, inside the Stone Tower mahito flatly declines his Great Uncle’s request:

mahito: “This wound (on his head) proves my malice. I won’t touch those stones (untainted by malice).”

mahito realizes he is “a human being harboring malice.”

Despite that, the only “stones” such a mahito would “touch” are not “the Great Uncle’s stones = stones untainted by malice,” but rather “stones the same as gravestones = stones of ‘malice’.”

To repeat again, in the manga version of How Will You Live, it states:

“We have the power to determine ourselves. Therefore we sometimes make mistakes. However – we have the power to determine ourselves. Therefore, we can also rectify those mistakes.”

Humans can “make mistakes” precisely because of that “power to determine.”

The reverse is also true – we can “rectify mistakes” because of that “power to determine.”

In other words, the act of “rectifying” only becomes possible after realizing one’s own “malice.”

(Realizing one’s “malice” = an opportunity to consider one’s own ethical standards)

For mahito, who learned this from the book (How Will You Live) gifted by his mother (Himiko),

The “stones of malice” are “stones of hope.”

It is by making mistakes that humans can rectify them.

Therefore, he will carry on living while embracing even his “malice (stones)” as part of himself.

(Only because Himiko accepted him together with his malice saying “You’re a good kid” can mahito go on living)

This action comes after mahito has learned and grown from the story so far.

[Side Note] Spiriting Away Trope – Memory Loss = Blue Heron’s “You’ll Forget Anyway”

In response to mahito asking about the pelicans, the blue heron scoffs:

Blue Heron: “You remember stuff over there? Hey, didn’t you bring anything back?”

Behind this dialogue lurks a common spiriting away trope.

4 Types of Spiriting Away Cases

1. Returns with memory intact

2. Returns without memory

3. Remains missing, never found

4. Corpse discovered

In other words, when someone returns from a spiriting away, there are two patterns regarding memory – having it (1) or not (2).

Since mahito brought something back (= stones and Kirico’s doll), he returns in state 1 (seemingly rare based on the blue heron’s reaction).

Blue Heron: “Oh well, never mind. You’ll forget it eventually anyway. See ya, pal.”

・ In the Stone Tower, mahito tells the Great Uncle “I’ll make some friends.” Hinting at future developments with “mahito made some friends.”

And with that the blue heron leaves, mahito and Natsuko reunited with the fathers who rushed over.

(Young Kirico also returns to grandma form from the doll and heads back together with them)

“You’ll forget eventually” is another common ending trope for spiriting away stories.

Epilogue – Returning to Tokyo 2 Years After the War’s End, With a Younger Brother Born Safe and Sound

After returning from the other world (= “Stone Tower”), Natsuko gives birth safely, and mahito gains a little brother.

The story beginning with

mahito: “In the third year of the war my mother died. In the fourth year we evacuated—”

concludes with

mahito: “In the second year after the war ended we returned to Tokyo.”

It’s a quiet ending linking the opening and closing with mahito’s narration, but

as explained up to now, mahito has grown significantly through his “malice.”

At this point, only two years have passed since the war.

The Tokyo welcoming back the evacuated mahito is probably no longer the Tokyo of old.

Issues like discrimination against atomic bomb survivors were probably just beginning to surface around this time.

While the serenity of the final scene hints at that grim reality, it also seems imbued with a powerful strength to make us viewers believe “mahito will be alright.”

[Consideration] “Add One of the 13 Blocks Every 3 Days” – The Great Uncle as Psychologist Carl Jung

The part I personally found most perplexing was the Great Uncle’s sections regarding the “Stone Tower.”

It took me six days of thinking since watching it (on opening day) to finally see clues to unraveling it, so I will explain and interpret that part here.

The Great Uncle’s “Stone Tower” – Connection to Psychologist Carl Jung

First, a brief explanation about the psychologist Carl Jung.

Carl Gustav Jung

– Born July 26, 1875 – Died June 6, 1961

– Swiss psychiatrist and psychologist who studied the unconscious and founded analytical psychology (Jungian psychology)

To briefly explain analytical psychology (Jungian psychology):

– Psychological analysis through word association games

– Analysis based on complexes

↑ In both cases, what analysis springs from is the “human unconscious.” By analyzing this, issues (like mental illness) can potentially be resolved.

There are a curiously high number of similarities between Jung and the Great Uncle that cannot simply be dismissed as coincidence.

I will list them below:

1. Constructing the “Stone Tower”

Great Uncle: One day stones fell from the sky. To protect them he builds the “Stone Tower.”

Jung: Contemplates the relationship between “self and stones” as basis for the relationship between “self and others.” Builds a “tower” to represent thoughts that cannot be fully articulated in words.

2. Victims While Under Construction

Great Uncle: “Many died” during construction of the “Stone Tower.”

Jung: “Corpses (skeletons)” appeared during construction of the “tower.” ※

※ Jung built two towers, the “first” and “separate.” When his eldest daughter came to the first tower’s construction site, she cried out “There are corpses here!” Then four years later, actual corpses were discovered at the separate tower’s construction site. Jung continued additions and renovations until he was 80.

→ In the film, the old woman reveals “Originally it was connected by a passageway to the main building (in other words, it was a ‘separate tower’), but collapsed and became isolated.”

3. “Rooms” Inside the “Stone Tower”

Great Uncle: Shuts himself alone inside the stone tower to read books. Before he realizes, he disappears.

Jung: Feeling something lacking, he builds a “separate tower.” Inside he creates a room where he can be alone ※, which Jung called “a place for spiritual concentration.”

※ Jung’s model for the room he envisioned was an Indian room. He sought a room for meditation.

↑ The corridor mahito passes through to reach the Great Uncle’s room resembles a Hindu temple corridor in India.

He built a “stone tower for his (thought) self,” “shut himself alone inside,” and disappeared.

Not only chronologically but in this respect as well, the Great Uncle shares common ground with Jung.

[Addendum] Interview Between Hayao Miyazaki and Bin Kimura

A famous Japanese psychologist was Mr. Bin Kimura (died in 2007). His specialty was “analytical psychology = Jungian psychology.”

In fact, Director Hayao Miyazaki has been interviewed ※ by Mr. Kimura in the past.

※ Published in The Collected Bin Kimura Talks 7: Stories and the Minds of Children

This is another reason why I link the “Great Uncle” (as depicted by Director Miyazaki) with “psychologist Jung” in my interpretation.

13 Stone Blocks = the 13 Years Since the Great Uncle Disappeared

Soon after the premiere, the theory proposing “13 stone blocks” as “the number of works Director Miyazaki has created” popped up online.

However, Miyazaki’s works consist of “directed works,” “written works,” and “pre-Ghibli works,” making it seem rather arbitrary to me

on what basis people are counting given such a mix.

Also, settling on “13 works” as the answer fails to address the in-world rule = setting of “add one every three days.”

So I contemplated my own answer instead.

In conclusion, the “13 stone blocks” represent the “Great Uncle’s 13 years.”

Timeline of Jung’s “Tower”

1923 – Jung’s “first tower” completed

※ For the Great Uncle, the “first tower” is the children’s main house.

1927 – Construction begins on separate (second) tower = Great Uncle’s “Stone Tower”

※ This is when corpses are discovered at the construction site.

1931 – Addition of “room where I can be alone” inside separate tower = room at the end of the corridor past the Great Uncle’s

Connecting this with events from mahito’s story:

Jung’s “Tower” x mahito’s Story

1927

– Jung begins construction on separate (second) tower = Great Uncle’s “Stone Tower”

1931

– Jung adds “room where I can be alone” = Great Uncle’s room is made

※ Year of Manchurian Incident (clash between Japanese and Chinese militaries, leading to Second Sino-Japanese War)

↓

1937

– Publication of Inazo Nitobe’s How Will You Live

↓

◇ First year of war

Dec. 1941 – Pearl Harbor attack

April 1942 – First air raid on Japanese mainland (including Tokyo) by B-25 bombers

↓

◇ Second year of war

↓

◇ Third year of war

Nov. 1944 – First Tokyo air raid by B-29 bombers

– mahito’s mother dies

↓

◇ Fourth year of war

– mahito evacuates (goes to “Stone Tower”)

March 1945 – Tokyo firebombing

Aug. 6, 1945 – Atomic bombing of Hiroshima

Aug. 9, 1945 – Atomic bombing of Nagasaki

Aug. 15, 1945 – End of war

※ Organized by “year of war” to match mahito in opening scene: “In the third year of the war my mother died. In the fourth year we evacuated.”

The important fact to note here is:

1931 – Great Uncle’s room constructed (year of Jung’s tower addition)

↓

1944 = Fourth year of war (Dec. 1944~Aug. 1945) – mahito evacuates

mahito evacuates precisely 13 years after the Great Uncle’s room inside the “Stone Tower” was created.

This is why I theorize the “13 blocks” represent the “13 years since the Great Uncle disappeared.”

Next I will examine the relationship between this fact and the setting of “add one every three days.”

Meaning of “Add One Every 3 Days” – Time Differential Via Spiriting Away = Inside and Outside the Tower

I theorized “the 13 blocks” = “the 13 years since the Great Uncle disappeared.”

Next I will explain why that takes the form of “add one every three days” (the rule stated by the Great Uncle to mahito).

The key point here is [Himiko’s Backstory].

Himi’s Backstory:

1. Himi’s great uncle visits the “Stone Tower” and disappears.

2. The “Stone Tower” is closed off/sealed.

3. Somehow, the “Stone Tower” reopens and Himi wanders inside (goes missing).

4. One year later, Himi returns looking exactly as she did when she disappeared.

In other words, Himi has been “spirited away.” The most well-known example of someone being “spirited away” is the story of Urashima Taro.

The Story of Urashima Taro:

1. Helps a turtle and visits the Dragon Palace (another world).

2. Happily spends time with the princess.

3. Returns to his original world.

4. Opens a jewel box and turns into an old man (shows the passage of time).

At first glance, it seems like the adventure story of the protagonist Urashima Taro. But from the perspective of the “original world,” this is a story of someone being “spirited away.”

Urashima Taro, who went missing, returns to the village decades later looking the “same as before” = “young.” (So the aged villagers don’t recognize him and Urashima Taro doesn’t recognize the aged villagers either).

The reconciliation of this time discrepancy is portrayed in the [ending] of the “jewel box” = “turning into an old man.”

Director Hayao Miyazaki’s 2001 film “Spirited Away” also depicts this “time discrepancy.”

Spirited Away:

1. Chihiro enters the world of the “bathhouse” with her parents (into another world).

2. Chihiro’s adventure and growth are depicted.

3. Guided by Haku, she returns to the original world.

4. The family car is covered in dust and the entrance gate has faded in color (shows time has passed).

While it wasn’t clearly stated in “Spirited Away,” the amount of time that had passed is clearly indicated by words in “The Boy and the Heron”

This is the line spoken by Himi’s great uncle: “I add one every three days.”

The key to unlocking this [setting] is the “13 blocks.”

If we assume “13 blocks” = “13 years since Himi’s great uncle disappeared,” then the explanation becomes clear.

[Reality]:

1931 – Himi’s great uncle’s room is built.

13 years later↓

1944 – mahito evacuates (happens 4 years into the war).

So in the “13 years” since the “room” was built, Himi’s great uncle has stacked up “13” stones.

In other words, he stacks “1 per year.”

Yet, he tells mahito “I add one every three days.”

Resolving this [contradiction] is the aforementioned depiction of the time discrepancy in tales of spiriting away (like Urashima Taro’s jewel box).

[Reality]: 1 per year

[Inside the Tower]: 1 per 3 days

Therefore, “1 year in reality” = “3 days inside the tower”

Time flows differently between [reality] and [inside the tower].

Supporting this in the story is the depiction of the “garden with four seasons.”

□ Garden with Four Seasons – A mysterious garden where flowers of all four seasons bloom simultaneously.

It appears in the medieval Japanese folktale “Urashima Taro.” When Urashima Taro opens four “East, West, North, South doors”, gardens with spring, summer, autumn and winter (in this painting’s case, cherry blossoms, irises, autumn leaves, and chrysanthemums) in bloom at the same time can be seen.

In “Spirited Away”, on Chihiro’s way to reunite with her parents (in pig form) guided by Haku, a “garden with four seasons” is depicted.

In “The Boy and the Heron”, it is subtly drawn into the garden that can be seen from the hallway mahito passes through on his way to his great uncle’s room after reuniting with Himi.

Applying “1 year in reality = 3 days inside the tower” also transforms how we see [Himi’s Backstory].

[Himi’s Backstory] from Himi’s Perspective:

1. Himi’s great uncle visits the “Stone Tower” and disappears.

2. The “Stone Tower” is closed off/sealed.

3. Somehow, the “Stone Tower” reopens and Himi wanders inside.

4. Three days later, Himi returns to the original world.

While it may have been “1 year” for Himi’s grandmother and the others in reality, it’s different for Himi who was inside the tower.

Just “3 days”, so of course she returns looking “exactly as she did when she disappeared”.

This is why Himi’s great uncle says “I add one every three days” and the “rule for spiriting away” in this work.

And “13 blocks” = the “13 years since Himi’s great uncle disappeared” gives clues towards finding this “rule.”

mahito calculates: 2 days = 8 months

Up until now, we’ve examined how time flows differently between [reality] and [inside the tower].

[Reality]: 1 per year

[Inside Tower]: 1 per 3 days

Therefore, “1 year in reality” = “3 days inside the tower”

The amount of time mahito spends inside the “Stone Tower” is “around 2 days” – “one day afternoon” ~ “next night※”

※ Stays overnight at Kiriko (Young)’s house the first day. Scene of heading to great uncle starting the next day at dusk.

[Himi’s Case]

Returns to reality after 1 year = Calculated to 3 days inside “Stone Tower”

↓

[mahito’s Case]

2 days inside “Stone Tower” = Calculated to 8 months after returning to reality

When mahito parts from Himi and returns to [reality], 8 months have passed.

8 months after in reality = End of war | Fighter plane windshields “cleaned up”

□ Date of End of War

August 15, 1945 – The end of war was announced to the public via an Imperial Rescript broadcast on the radio at noon, informing them of Japan’s acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration decided the previous day and Japan’s surrender.

The Japanese government issued orders to the military to disarm and surrender to the Allied forces of America, Britain, China and others who also stopped combat accordingly.

[Beginning]

mahito: “My mother died in the third year of the war. In the fourth year, I was evacuated.”

– 3rd year of war = Dec 8, 1943 – Dec 7, 1944

– 4th year of war = Dec 8, 1944 – Aug 15, 1945 (end of war)

mahito had been evacuated to Natsuki’s during the “fourth year of the war”.

Since Japan welcomed the end of the war during this fourth year, it was a period of around 8 months.

In other words, when mahito returns, “Japan has lost the war = the war is over”.

This is portrayed through mahito’s father.

[mahito’s Father]

One day, carries large quantities of fighter plane windshields into a room in the estate.

Says “Couldn’t leave so many at the station, so got a room to store them”.

↓

Later, subordinates carry the windshields out of the room.

mahito and Natsuki’s fruitless search is depicted.

↑ Father declines offer of “Shall we help?” from subordinate and tells him “Go rest” instead. Reunites with mahito (mahito returns)

The reason mahito’s father brings in large quantities of fighter plane windshields is because they were necessary inventory for the war.

But given that it’s after the war, the meaning changes completely when they’re carried out.

“War is over” = The military received orders from the country to “disarm”.

→ Guns and fighter planes became unnecessary.

In other words, the depiction is of mahito’s father “clearing up” the windshields.

[Notes] Unused Fighter Planes | Kamikaze Special Attack Units

If we assume mahito’s return is after the end of the war, then his father is “clearing up” (windshields) fighter planes as analyzed.

If we take this analysis to be correct, the following historical fact also seems to be depicted in this work:

□ Kamikaze Special Attack Units

(Kamikaze Tokubetsu Kōgekitai)

1 Abbreviated as “Kamikaze”

2 Attack units organized by the Imperial Japanese Navy during WWII

・ Comprised of a special attack unit carrying out suicide crashes using bomb-loaded aircraft, and a unit responsible for providing direct cover and confirming results.

・ Attack targets were warships

3 Having lost a large number of combat-ready aircraft in the Battle of Okinawa, the Navy also used aircraft impractical for combat (trainer and reconnaissance seaplanes) for special attacks.

・ The aircraft with the greatest numbers still remaining at the end of WWII were 2,791 Kyushu K11W Shiragiku (includes seaplane trainers).

・ Second most numerous was 1,017 Zero Fighters ← The windshields mahito’s father manufactures are likely for Zero Fighters based on their shape

4 Although the Kamikaze Special Attack Units continued until Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945, the large numbers of special attack aircraft prepared for decisive homeland defense never got to sortie.

With this additional context, looking at mahito’s father’s [scene] again may allow one to pick up on things not visible the first time.

【Reference site list】

・君たちはどう生きるか – スタジオジブリ|STUDIO GHIBLI

・TOHO THEATER LIST/君たちはどう生きるかシアターリスト

・君たちはどう生きるか : 作品情報 – 映画.com (eiga.com)

・「君たちはどう生きるか」分かっていることまとめ ジブリ単独出資、「シン・エヴァ」に内定していた作画監督 : ニュース – アニメハック (eiga.com)

コメント